A whole lot of years ago [I was a kid] I discovered that there had been two [at least] Sandman stories that were supposed to have been published in the Book of Dreams anthology, and for whatever reason they were not. I found these around the web together with the notes from their authors explaining how they had received not the best treatment from the publishers, and how their stories had simply been omitted with no clear explanation.

I found both of these stories quite enjoyable and saved myself copies of them. Recently during a conversation with some friends one thing lead to the other and we noticed that neither story seems to be online anymore [as SFF, the website which used to host them, has been taken offline]. So it was suggested I should post these here on our little scrapbook, so that they will be easier to find for people. If there is still a copy of any of these somewhere else online in a more official capacity, or if the authors wish them taken offline, please let me know. Also if you have links to the artists’ current homepages, blogs or anywhere else they publish, that would be nice to have too.

These are exact copies of the stories and notes, down to the last punctuation. It’s my understanding that they were originally published some time during 1994 – 1996.

P.S.: Yes, I’m aware of the Spanish booklet.

Merv Pumpkinhead’s Big Night Out by Michael Berry – Author’s Notes

The Voice of Her Eyes by Karawynn Long – Author’s Notes

Merv Pumpkinhead’s Big Night Out by Michael Berry

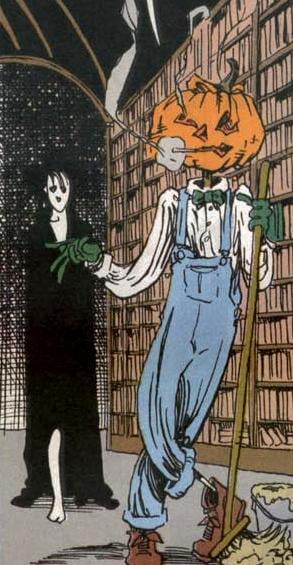

Illustration by Jill Thompson and Vince Locke. Dream and related characters (c) DC Comics

I don’t know about you, but my two favorite words in the English language are “quittin’ time.”

You spend the whole freakin’ week busting your butt: painting skies, schlepping books from one wing of the castle to another, fishing the evilest kind of crud out of the plumbing, trying to construct an orrery when you don’t have a clue what the hell an orrery is supposed to be. Seems like you’re never going to get to the bottom of the job orders, even if you work twenty-seven hours a day.

Stress City, pal. I get migraines like somebody’s carving my head with a woodburning kit.

Construction’s a demanding trade, a science almost, but do you think anybody appreciates that fact? Forget about it. All you’re ever going to hear is how the doorway to the laundry room is thirteen degrees off plumb or that you’ve connected a sewer main to somebody’s hot tub. The stuff you do right, they never notice.

That’s why I’m so jazzed when the five o’clock whistle blows at the end of the week. My time’s finally my own. For the next forty-eight hours, nobody’s gonna be telling Merv Pumpkinhead what to do. I punch the time clock a good one across the chops, and I’m out of there without another look back.

Last Friday, after quittin’ time finally came around, I was getting my lunchbox out of my locker. Boris, one of the regulars on my crew, came up behind me and said, “Hey, Merv. Me and Tiny are going to grab a couple of six-packs and head over to his place. He’s got cable and the George Raft-Hedy Lamarr version of ‘Casablanca’ is on tonight. Want to come along?”

Now, I like Tiny and Boris. They’re good, honest joes, salt-of-the-earth. But, cripes, I’m stuck with them all week long. Enough’s enough. Besides, when you’re in a supervisory position like I am, it’s not smart to get too chummy with the hired help. They’ll just try to take advantage later. Trust me on this.

So I said, “Thanks, but no thanks. I’ll see you guys on Monday. Have a good one.”

To tell you the truth, I had bigger plans than sitting around with those palookas, swilling cheap brew and watching Ronald Reagan as Viktor Laszlo. For the first time in I don’t know how long, there was going to be a card game. A real, no-kiddin’-around card game. Just what the doctor ordered to cure those Workaday Blues.

I went back to my place, put on a fresh pair of overalls and packed a duffel bag of necessities, including some items to barter in case I ran out of cash on the barrelhead. Since we’d agreed that I’d bring the beverages to the game, I also loaded a wheelbarrow full of bottles, cans and ice and headed off. You never know what people are going to want to drink around here, so I’d stocked up on everything from absinthe to Moxie in a two-liter jug.

I was a little late getting to the House of Secrets, having hit a damn pothole on the way and spilled everything in the road. Abel answered the doorbell right away, saying, “Cuhcome in, MuhmuhMervyn. Everybody’s huhhere.” He was all sweaty, his beady little eyes darting all over the place, his jowls quivering

“Your brother around?” I asked.

“Nuhnuhno. Cain’s, uh, guhgone on an errand. He won’t be back until tuhtomorrow night.” He grabbed my sleeve and pulled me inside. “Come on. Huhhuhhurry.”

Some folks think Abel’s place is a dump, but I kinda like it. It’s got personality. It’s also got tons of cobwebs, splintery boards in the floor, skulls on the bookcase, a stuffed crocodile hanging from the ceiling, weird-ass collector’s items from every time and place imaginable, and something you don’t even want to think about living in the basement. But hey, it’s a damn sight more comfortable than some of the fancy-schmancy quarters at the castle, full of marble that’s got to be polished and Persian carpets that need to be vacuumed every hour on the hour. At Abel’s house, nobody’s going to yell at you if you rest your feet on the coffeetable.

Abel had set up a cardtable in front of the fireplace, and three guys sat around it, diddling around with their chips and not bothering to talk to each other. I recognized two of them right away.

“Hey, Ruthven,” I said to the giant, fanged rabbit in the frock coat. “How they hangin’?”

He nodded at me. “Mervyn. Always a pleasure.”

The fat man with the broad-brimmed hat, green vest, drooping, gray mustache and wire-rimmed, pinch-nose spectacles said, “Hola, Mervyn. It’s good to see you again. Pull up a chair and join us.”

“Don’t mind if I do, Fiddler’s Green, old bean.”

I’d never seen the third player before, not in any part of the Dreaming. He was muscular, blond and young-looking, though of course that don’t mean a thing. He wore a blue, double-breasted suit with yellow pinstripes, a red tie, two-toned shoes and a green fedora. Very sporty in a “Luck Be A Lady Tonight” sorta way.

He didn’t seem eager to introduce himself, so I stuck out a hand. “Merv Pumpkinhead’s the name, seven-card tarot’s the game. How’s it going?”

“Fine, thank you, Mervyn.” We shook. He had a grip like a pair of needle-nosed pliers. “You may call me Herman.”

“Nice ta meetcha, Herm.”

He squeezed harder, enough to break the bones in my hand, assuming I had any. “I said, you may call me Herman.”

“Okay, okay. No problem. Jeez.”

I got my mitt away from Mr. Congeniality and sat down. Something under my butt went “Meep!” I got up quick and found Abel’s pet baby gargoyle on my seat. “Sorry, Goldie. Didn’t see you there.” The little yellow critter hopped down and went looking for a safer place to roost.

Abel came to the table, a fresh deck of cards in hand.He said, “I’ve buhbeen, er, umm, looking forward to this all wuhwuhweek. We, uh, we huhhaven’t done this in ages.”

Fiddler’s Green said, “Hoom. Not for half a century or more.”

I said, “All we need is Brute and Glob, and it’d be just like old times.”

“Brute and Glob,” said Ruthven. “A disagreeable pair, indeed. But I rather miss their antics.”

I kinda missed them, too, to tell you the truth. Brute was dumber than a wet sack of fertilizer and not any prettier. Glob cheated like a son-of-a-bitch, but if you didn’t mind getting fleeced every once in a while, you could learn a thing or two from him.

I wouldn’t wish what happened to those two numbskulls on my worst enemy. But that’s what you get when you try to pull a fast one on the boss. One strike, and you’re out.

Abel opened the deck of cards and did a couple of sloppy shuffles. We drew to choose the dealer, and Fiddler’s Green got the high card. We were off.

I got a crappy hand, so I folded early and watched the others battle it out. I’d tumbled to Abel’s and the Fiddler’s tells decades ago (Abel’s sweat glands go into overdrive when he’s bluffing, and the “hooms” come fast and furious when the fat man’s on a roll), but Ruthven keeps a real poker face. Those red eyes give away nothing.

Herm the Germ, of course, was a complete mystery, and I wanted some clue about his strategy. Nothing obvious caught my attention, though. He didn’t tap his toes or whistle or bite his nails, just sat there with his back straight and his eyes on the cards. When the hand was over, it was Herm who came up the winner, his full palace beating Ruthven’s pair of knights.

Herman chuckled and rubbed his hands together as he raked in the chips. “The evening is off to a most satisfying start. You may take this as a portent of things to come, gentlemen.”

I said, “Just shut up and deal, willya?”

While he shuffled, I reached into a pocket and pulled out my cigs. I was all set to light up, when Herman shot me a look and said, “Do you mind?”

“Do I mind what?”

“I would prefer if you didn’t smoke. I find the habit offensive in the extreme.”

“Pardon my French, but excusez-moi.” I looked around the table for support. “Whaddaya say, guys? Am I within my unalienable rights here, or what? Abel?”

“Uhh, err, I, thuhthat is, uh –”

“Never mind. Ruthven?”

Ruthven’s pink little nose twitched.. “Actually, it is difficult to get the smell out of my fur.”

“Fiddler’s?”

“Hoom. Quitting would do you a world of good, Mervyn. Nicotine plays havoc with one’s constitution.” He rooted around in his carrybag. “Perhaps you’d care for a few jelly babies instead?”

I considered telling him that losing ninety pounds or so would do wonders for his own freakin’ constitution, but there was no point in being nasty. So I just stashed my pack and said, “All right, all right. I’m out-voted. But I want you to know that you’re all turning into a bunch of old ladies.”

We played for about two hours without a break. Herm didn’t win every hand, only four out of five. Ruthven and I took a couple of pots each, but Lady Luck never smiled once on either Fiddler’s Green or Abel. The fat man’s wagers never went beyond the penny-ante, so he was still in pretty good shape, but after hemorrhaging chips for a hundred and twenty minutes, Abel was down to his last half-dozen.

I figured it was time to put a chill on Herman’s winning streak. “How ’bout we take a break, guys? I could use a stretch, a smoke and a can of brew.”

Everyone except Herman was quick to agree. We put down our cards and moved to the buffet. It was a pretty good spread. Fiddler’s Green and Ruthven had done the catering. Sometimes their hoity-toity tastes get the better of them, but there was still plenty of stuff for a meat-and-potatoes man like myself. I managed to put together one beaut of a sandwich, a triple-decker with roast beef, salami, sardines, Limburger, tomato, pickles, horseradish and sweet Bermuda onion.

I caught Herman staring at my selection of drinks. His upper lip was wrinkled like he’d been offered a cup of raven’s droppings.

“Nothing suit your fancy, Herman?”

“Mmmm, no. I’m afraid not. I’ve been looking in vain for a glass of nectar.”

I pulled two 12-ounce cans out of the ice. “What do you mean? We got guava nectar. We got mango nectar. Take your pick.”

“I’d rather not.”

Glass in hand, Fiddler’s Green said, “May I recommend the tokay? It’s quite fine.”

Herman sniffed. “Perhaps another time.”

That was all I could take. Out on the porch, I cornered the host. “Hey, Abel, who the hell invited that bozo? He a friend of yours?”

“Huhherman? Er, uh, no, no. He arrived with Ruthven.”

Ruthven doesn’t have any friends. He spends all his time flirting with that broad in the hoop skirt. I told Abel as much.

“Wuhwell, Lucien was supposed to join us tonight, but he cancelled at the last minute. Uh, uh, muhmaybe he knows him.”

“I doubt it.” I fired up a smoke and took a long, delicious drag. “There’s something mighty fishy about this chump, and I don’t like it. Not a freakin’ bit.”

Right on cue, Herm came out to join us. Actually, he did his best to ignore me, homing in on Abel, saying, “Bad bit of luck you’ve been having, my friend. Perhaps you’ll fare better once we resume.”

“I huhhope so.”

“Quite the place you have here,” Herm went on. “A veritable treasure trove of antiquities and ephemera. Would you mind showing me around?”

“Of cuhcourse not. It would be my puhpleasure.”

Herman steered Abel back inside, leaving me alone with my cig, my sandwich and my thoughts. The first two were great, but the last were giving me major indigestion. Without saying a word to anybody, I set off on a little walk, down past the graveyard and up to a little cave I know.

I got back just in the nick of time. As I closed the front door behind me, Ruthven and Fiddler’s Green were in their seats at the cardtable, and Herman and Abel were coming down from a tour of the attic. Nobody asked where I’d been, and I didn’t offer any hints.

It was my turn to deal. I executed a spiffy little shuffle and passed ’round the cards. For once, my hand wasn’t complete garbage, giving me a fighting chance of winning.

Ruthven and Fiddler’s Green folded early, but I could tell from the slick of sweat on his forehead that Abel thought he had a hot hand. I wanted to kick him under the table, but I wasn’t sure either of my aim or that Abel wouldn’t yelp like a goosed schoolgirl. Herman, a chilly little grin on his puss, kept raising the stakes, and Abel kept right on matching them, down to his last chip.

When they turned their cards over, it was Herm’s hand that was full of royal portraits.

Abel looked ready to cry. “I-I guhguess I’m done for the nuhnight,” he said, starting to get up from the table. “Muhmight as well get a start on the duhdishes.”

Herman reached around, grabbed Abel by the shoulder and pushed him back down. He asked, “What’s your hurry, Abel? We’re all friends here, correct? I, for one, would be happy to advance you a small sum so that we can continue to enjoy your company at the table.” He deposited a stack of chips, probably two dozen or so, in front of Abel. “Is this a sufficient quantity?”

Ruthven, Fiddler’s Green and I were all looking at each other, silently asking “What the flick is goin’ on here?” but Abel didn’t notice. He said, “Thuhthat’s very kind. Buhbut I don’t know if I shuhshould.”

“Of course you should. In fact, I insist.”

Fiddler’s Green spoke up. “If Abel is uncomfortable accepting your debt, then I don’t think–”

Herman cut him right off. “Abel is quite capable of looking out for himself. I mean, despite what you three and his brother happen to think.”

Abel gave a little start. “Duhduhdo you know Cuhcain?”

“Oh, yes, quite well. I’m surprised you didn’t invite him tonight. He’ll be so disappointed when I mention to him that you waited until he was out of town to throw this party.”

Abel’s eyeballs inflated to nearly twice their size. Given his brother’s homicidal tendencies, I didn’t blame him one bit for being scared.

“You wuhuwouldn’t do that, wuhwould you? Puhpuhplease, there’s no nuhneed to say anything to Cuhchcain!”

Herman said,”Well, perhaps not. Still, the night is young, and I’m not yet ready to call it quits. Please accept the loan. I happened to notice a couple or three items in the house that can serve as suitable collateral.”

I should have tumbled to it earlier, but suddenly everything made sense. “Hold it, pal,” I said. “Just who the hell do you think you are? ”

Herman didn’t even bother to glance my way. “I don’t believe this is any of your business, Mervyn.”

“Oh, yeah? Well, I’m not going to stand around with my thumb up my butt while some out-of-town sharpie cheats a compadre out of what’s rightfully his. This whole game has been one long con, a scam to get your hands on some of Abel’s best-kept merchandise, right?”

“I have no idea what you’re talking about. I’m here to enjoy a simple game of cards. I have no interest in taking what isn’t mine.”

“Hey, bub. Everybody wants secrets. Don’t kid a kidder.”

Herm turned his attention to Ruthven and Fiddler’s Green, who were just sitting there, taking it all in and doing their damnedest not to choose sides. “What would you have me do? Are you inviting me to leave? That’s fine, but I’m afraid poor Abel may later rue his lack of consideration for his brother’s feelings.”

I wanted to take this guy to the cleaners, bad. “How’s this? Why don’t you play me, one-on-one, no limit, winner takes all?”

He pointed at my pile of chips and said, “That is nothing but pocketchange to me. What else do you have that I could possibly want?”

“Well, let’s just see, OK?”

I reached into my duffel bag, rooted among my emergency supplies and came up with something I’d been saving a long time, from the days when the boss was locked up, the Dreaming was a shambles and I was out in the world, scratching a living.

I asked, “Interested or no?”

He didn’t actually lick his lips, but he couldn’t hide his interest. “May I examine it? This would not be the first time someone offered me a counterfeit.”

“Go right ahead.”

He looked the small statue over and, when it passed inspection, said, “Wherever did you get it?”

I shrugged. “I used to drive a bus. Folks leave the damnedest stuff behind. You ready to play?”

“Yes.”

“Sky’s the limit,” I said. “If you walk out the door empty-handed, you don’t bitch about it later.”

He gave it a second’s thought, then nodded. “Fair enough. Let’s go.”

Abel brought us a fresh deck, and we cut for the deal. Herm got the high card. I took my seven cards and made sure I didn’t wince when I got a gander at them. Not a hell of a lot to work with, but I figured to make the best of it. I took two cards. Herm took three, definitely a good sign.

Back and forth it went. I got the cups and wands I wanted, but I was weak in the Major Arcana. But finally it came down to put up or shut up. If I didn’t match his bet, I lost.

“Well, Mervyn,” he said. “Are you going to play or do you fold?”

He was bluffing. He wasn’t bluffing. I couldn’t tell. Ever so carefully, I let my gaze wander upward, to a point just over Herm’s left shoulder. I saw what I needed to see without anybody seeing me see it, if you get my drift.

“No way in Hades I’m gonna fold.”

Herman turned his cards over. “Let’s see if you can beat that.”

“Oooh-kay!” I said, unveiling a gorgeous run of high-value pasteboard. “Read ’em and weep, Herm. Read’em and weep.”

Nobody said anything. All you could hear was the tick of the grandfather clock and the growl of Fiddler’s Green’s belly. Then Herm got all red in the face, smashed his fist down on the table and stood up so fast that his chair skidded across the room, smacking into the bookcase behind him.

Something up near the ceiling went “Kaarkk!,” followed by the flutter of wings and a muttered “Oh, shit!”

Everybody whipped around and stared at the raven trying to regain its balance on the horned skull that sat on the bookcase’s top shelf.

Leave it to Abel to not know when to keep his big trap shut. “Muhmatthew!” he said. “Wuhwhat are you doing huhhere?”

I wanted to disappear through a hole in the floor, but none of them was quite big enough.

Herman twigged to the situation real quick. “You underhanded little bastard. I was right, afterall. I knew you were a cheat the moment I saw your orange, empty head.”

“Heh, heh. You might be jumpin’ to an erroneous conclusion here, Herman,” I said. “You see –”

“Spare me.” He did something — traced a pentagram in the air, twitched his eyebrows, wiggled his nose, happened so fast I couldn’t quite catch it — and suddenly he wasn’t costumed like a chorus boy from “Guys and Dolls” anymore. Nope, now he looked like a refugee from a frat party, dressed in a toga and a wide-brimmed hat. In one hand he held a stick with a couple of live snakes twisted around the top of it, hissing into each other’s faces. He’d also traded his Florsheims for a pair of little sandals with wings.

He said, “You asked who the hell I think I am, Mervyn Pumpkin. Well, let me tell you exactly. My name is Hermes. Messenger of Zeus. God of travel, of luck, of healing.”

Fiddler’s Green said, “Of gambling, of commerce, of thievery.”

Hermes ignored him. “I am here in the Dreaming at the invitation of Lord Morpheus. That’s right. These days I ply my trade between the worlds, tracking down lost treasures, bartering them among my many customers. Today I supplied your master with an item he had long been seeking, an act for which he was exceedingly grateful.”

He hooked a finger under my bowtie and yanked me forward until his face was an inch from mine. He said, “Do you think Morpheus will be pleased with the singular lack of hospitality you’ve shown me?”

Man, oh, man. I knew the answer to that the way I know my own name. Rules of etiquette are a big freakin’ deal to the boss. Seems like people get banished to the Eternal Darkness for using the wrong fork around here. I had a feeling the next words out of my mouth would sound something like, “Homina, homina, homina.”

But somebody else spoke up before I could. A voice croaked, “Not so fast!”, and Matthew swooped down and landed on Hermes’ shoulder. Before Herm could swat him away, the raven stuck his head up his left sleeve and came out with two cards in his beak, a hierophant and a hanged man.

Fiddler’s Green took them and said, “Hoom. What have we here?”

Now it was Hermes’ turn to go kind of greenish. “I have no idea how those got there.”

Matthew said, “I’m no eagle, but I know what I saw. You slipped them up there while Abel was searching for a fresh deck.”

Ruthven said, “It looks as if Mervyn isn’t the only one guilty of bad manners.”

“Hoom,” said Fiddler’s Green. “I’m not certain Lord Morpheus would approve of your behavior, either, Hermes. Perhaps it would be best all around if we practiced a degree of discretion and said nothing further about this matter.” He looked pointedly at our host. “Right, Abel?”

“Yuhyuhyes. Shuhshuhsure.”

Hermes mulled it over before saying, “Then I will take my leave.” He scooped his winnings into a sack tied to his belt.

I could breathe again. “So, we’re even, Herm,” I said, giving him a friendly pat on the shoulder. “No harm, no foul. Let’s let bygones be bygones.”

He stared at me at long time, and the snakes-on-a-stick hissed like they wanted to spit hot poison in my eyeholes. “I don’t believe in bygones, Pumpkinhead. You would do well to tread carefully from here on out.”

He left without slamming the front door.

“Good riddance,” I said. “We still got time for a couple more hands. Everybody still up for it?”

Abel’s phone rang.

“Muhmummervyn, it’s for yuhyou!”

“Criminy! Now what?”

Seems like someone hadn’t tightened all the screws after installing a new chandelier in the ballroom. I had to split and supervise the mop-up.

Before I left, though, I gave Matthew the statue Hermes had had the hots for. What the hell, he’d kept my ass out of the fire, and I owed him one. Besides, I thought the figurine was a pretty good likeness of him.

Matthew keeps it up on a shelf in his cave. He says it’s not a raven, though, but a falcon. Whatever. I got more important things to think about.

(c) 1994 by Michael Berry

Michael Berry’s notes:

A number of years ago, I submitted this piece to the editors of a proposed anthology of short stories based on Neil Gaiman’s outstanding “Sandman” comic, published by DC Comics. After a reasonably short while, I received word that the editors wanted to buy it. I signed a contract (a very odious one, but that’s another story…) and was told my manuscript was being forwarded to DC Comics for final approval. A year or so went by without any further communication. And then one day I received an envelope containing my contract, a check for a kill fee, and no other word of explanation. How puzzling! How rude!

The folks at fault are not the editors, who have been thoroughly professional, but the people at DC, who have been anything but. There’s no use moping about it, even though the story is unsaleable to any other market. So here it is, available to you, free of charge.

I’m not the only writer to have been treated shabbily by DC during the course of this project. You can obtain another perspective on the debacle from Karawynn Long. Read her fine story about Delirium and contemplate the book that might have been…

The Voice of Her Eyes by Karawynn Long

The texture of the carpet caught her first. Lucy was down on her hands and knees, feeling under the bookshelves for a doll’s shoe that one of the kids had lost. As she ran her hand lightly over the carpet, the individual bumps and nubs grew distinct under her fingertips, like a message in Braille that she could almost comprehend.

She pulled out a battered crayon and a scrap of dirty paper, but no plastic shoe. Lucy bent down farther, tilting her head sideways to peer under the bottom shelf of the bookcase, on the chance she’d missed something.

And she saw colors. The drab old carpet was full of them. Curling loops of turquoise, gold, mauve, orange, lavender, and rose. Sky blue, maroon, green, teal, lemon yellow. Dozens and dozens of colors, many that she had no names for — a shade between the rose and the maroon, with just a hint of lavender …

“Lucy —”

She pushed deeper into the colors, or they grew larger around her, until they filled her vision entirely. Her eyes searched for a pattern in their placement, repetitions too vast to be obvious. The colors were compelling, fascinating, promising safety and escape …

“Lucy!”

She blinked once, pulled her eyes into focus, and looked up. A woman stood above her, tall and angry. The awful pressure flooded in upon her then, a roaring inside her ears and something invisible pushing against her head. Or not quite invisible. Silvery-dark shapes grew and shrank like moire lines in the corners of her eyes.

Squeezing them shut, Lucy did something which felt like thrusting back against the pressure, until it receded. When she opened her eyes again it was only Margaret standing over her, with the half-worried, half-exasperated expression that she often wore when speaking to Lucy. “What are you doing down there?”

Lucy sat up and shrugged. “Looking for one of the doll shoes.” She had only been working at the day care for two weeks, but already she had learned that it was impossible to explain to Margaret about things like colors in the carpet.

Margaret still looked unsatisfied, but Lucy could see her decide that it wasn’t worth pursuing. “You remember we have a new student this morning, a girl named Katie,” Margaret said. “I asked her mother to bring her early so we’d have a chance to talk and show her around the room before the other kids arrive.” Margaret looked at her watch. “They should be here any minute. Actually, they should have been here ten minutes ago.”

Lucy stood up, bracing one hand on the bookshelves. A new girl. Some of the kids would probably try to pick on her. Matthew, in particular. “Did you tell her to wear paint clothes?”

Margaret frowned. “Oh, dammit, no. I forgot. Well, she can wear something from the box.” The tin bell on the front door jangled as it was opened. “That’s probably them,” Margaret said, hurrying out of the room.

Lucy glanced down. From this height, all the bright varied colors of the carpet blended together into the muted, nondescript shade of brownish-gray she was accustomed to. She resisted the urge to get down again and make sure that the colors were still there.

Margaret returned, followed by an elegant woman in a business suit who was holding the hand of a brown-haired little girl in a white blouse and red corduroy jumper.

“Hello,” the woman said to Lucy, without waiting for Margaret to introduce them. “You must be … Ms. Turnbridge? I’m Ellen Bartholomew, and this is my daughter Katie.” Ellen’s tone was faultlessly polite, but she hesitated, glancing at Lucy’s paint-daubed jeans and t-shirt.

Lucy ignored the mother and squatted down in front of the child. The girl was thin to the point of fragility, large brown eyes eloquent in the small face. “Hi,” Lucy said solemnly. “I’m Lucy. What’s your name?”

“Kate.” Her voice was so soft it would have been easy to mistake, but Lucy was paying careful attention.

“Kate,” she repeated, and was pleased to see a spark of interest in the girl’s eyes.

Ellen broke in then, with a tug on Kate’s hand that made her take a step back from Lucy. “Katie, you remember what I told you in the car. You do exactly what Ms. Valdez and Ms. Turnbridge tell you. If I hear that you’ve been any trouble whatsoever, you’ll be in a lot more trouble when you get home. Do you understand?” She jerked the girl’s hand again to get her attention.

“Yes ma’am,” Kate answered, looking down at the carpet.

Lucy was torn. She wanted to take Kate’s other hand, but she worried that it might make her mother cling harder, or that it would seem threatening or controlling to Kate. What she really wanted was for the mother to leave as soon as possible, so that maybe she could get Kate to relax a little.

Fortunately Margaret broke in. “Lucy, would you show Katie around the room while I get Mrs. Bartholomew to sign a couple of papers?”

“Sure,” said Lucy. She stood up, decided against offering Kate her hand, and waited. Ellen brushed her hands over the girl’s hair, which wasn’t messy, and straightened her jumper, which hadn’t been crooked. “You be careful with those new clothes, now,” she warned the girl. “Don’t get them dirty.” Lucy winced internally but kept her face impassive. Ellen followed Margaret out of the room, leaving Lucy and Kate alone. Lucy smiled at Kate for the first time, then, and tried not to be disappointed when she only stared back.

“Why don’t we —” Lucy began, then broke off as Andy barrelled into the room, shouting her name. He ran up to her and wrapped his arms around her legs in an enthusiastic hug.

“Hello, Andy.” Lucy patted his back and then pried his arms off. “Andy, I’d like you to meet a friend of mine, Kate. Kate, this is my friend Andy.”

“Hi,” said Andy. “Lucy, can I do the calendar today? Please?”

Lucy sighed. Kate had turned around and was looking at the books. “Andy, you know we go by turns. You can do the calendar when it’s your turn.”

By then the other kids were straggling in, and Lucy had her hands full getting everybody settled. She pulled an extra chair one of the round tables for Kate, putting her between Andy and Shanika and across the room from Matthew. Lucy introduced Kate quickly and swept right into the morning routines, before the girl could feel too uncomfortable being the focus of attention. They did the counting off, and the calendar, and fed the fish. While the kids stood clustered around the aquarium, Lucy noticed Matthew sidling up towards Kate with mischief all too clearly in mind.

Lucy sighed and sent them all back to their seats. She asked for stories of things that had happened yesterday, and made sure every kid who wanted to speak got a turn. Most of them wanted to explain the plots of TV shows, which Lucy bore with suppressed annoyance.

Finally it was time for the big morning activity. “Did everybody remember to wear their paint clothes today?” she asked.

This provoked a ragged chorus of yeses, escalating as the kids began to compete in loudness. Rather than trying to shout at them over the rising din, Lucy sat — dropped without warning straight down behind the table as though she had fallen through a trap door. The unexpected movement caught the kids’ attention. As their voices trailed off, she heard one cheerful fearless “no” on the left.

“Who said no? Matthew?” She popped her head up over the table’s edge just to the level of her eyes. Several of the girls giggled, and Matthew nodded his blond head vigorously. “Okay, then Matthew needs to go pick out a t-shirt from the play-clothes box. Will you show Kate where the box is so she can pick out a t-shirt too?” Matthew nodded with self-importance and stood up, waiting for Kate, who froze under the sudden attention.

Several places away, Amy half-stood in her chair and leaned forward over the table, wiggling her hand. “Lucy, I need to pick out a t-shirt too.”

Lucy checked Amy’s clothes, but her denim overalls bore the marks of previous paint sessions. The other kids watched intently, poised to insist on their own t-shirts. From the corner of her eye, Lucy saw Kate stand up and follow Matthew. “Amy, I know what you need more than a t-shirt.”

Amy sat down partway and thought about that. “What?”

“You need to paint a bright orange flower right on the front of those overalls you’re wearing.”

Amy ducked her chin into her neck and peered down at her front. “Okay,” she conceded. “But I want a yellow flower, to match my clip.” She fingered the plastic barrette that held back her curly black hair.

Under the windows, Matthew was making a big show of holding the stack of play-clothes for Kate while she pulled a shirt from the bottom of the box. Lucy smiled. “That’s a good idea,” she said to Amy.

“Okay, let’s get started.” Lucy called up two kids to pass out the sheets of wax paper and paper towels for wiping fingers. She opened the plastic jars of tempera paint herself and scattered them around the two tables.

Lucy let the kids play with the paints for a little while on their own, only listening to make sure the squabbles over who-had-what-color didn’t get out of hand. Then she began to circle around the room, looking at the different pictures and offering encouragement.

She came up first behind a girl with dark hair in two pigtails. On one side of her paper was an unidentifiable eccentric smear of black and white and grey, with two odd smudges of red and hot pink; on the other was an irregular blotch of deep and vivid blue.

“It’s a pumpkin,” Lisa explained anxiously. “Jamie kept hogging all the orange.”

On impulse, Lucy tilted her head and tried to focus on the picture in that particular way, the way that revealed all the different colors in the carpet. The blotches and lines blurred further, then resolved into recognizable objects. “I see,” she said. “A fat blue pumpkin. Oh!” She smiled as she recognized the other shape. “And a glass cat sitting next to it, washing her face with one paw. You can even see her pink brains. That’s very pretty, Lisa.”

Lisa was staring up at her, astonished; when Lucy met her eyes she broke into a delighted grin. Lucy grinned back and moved on to the next one.

Most of the other pictures were more abstract, the kids just having fun with the feel of the paint on their fingers or the way two colors blended together. Kate, however, had taken all the bright cheery paint colors and mixed them together until her whole paper was covered in a huge muddy swirl of brownish purple. A few streaks of red and yellow had escaped around the edges, and Kate was now busy systematically covering each of them over with the dull purple-brown. It was disturbing. It was the opposite of finding colors in the carpet, Lucy thought, and almost in the same moment understood that she was afraid to look too closely at Kate’s picture. A hard knot formed in the pit of her stomach just thinking about it.

She couldn’t even come up with anything nice or encouraging to say about the girl’s effort, though she knew her silence would be noticed and she felt guilty. Lucy laid an affectionate hand on Kate’s head as she passed by, and felt hurt and even more guilty when she ducked away.

When the kids began to exhibit more interest in painting each other than the wax paper, she had them leave the pictures on the tables to dry and line up in front of the sink to wash the paint off of fingers, arms, elbows, and noses. Lucy let them do it themselves but stood by to help, scrubbing with a damp paper towel at places the kids didn’t see or couldn’t reach. Kate, because she’d had to wrestle out of the oversized t-shirt, was last in line. She climbed the stool and washed her hands very thoroughly without help. As she turned away, though, Lucy glimpsed a brownish-purple smudge on the back of one thin arm.

“Hang on a sec,” Lucy said, and caught the girl’s shoulder. Kate breathed in sharply and twisted, trying to get away. “Hey, be still,” Lucy said in surprise. “You missed a place back here.” With her other hand she stretched over and grabbed a clean paper towel, ran it under the trickle of water and began to rub at the spot.

She’d barely touched Kate’s arm when the girl whimpered in pain and tried to pull away again. Shocked, Lucy let go of Kate’s shoulder and stared after her as she ran partway across the room and stopped, uncertain. Lucy thought she could feel the pressure again, still far away but waiting.

At that point, she almost let it go, but the memory of the girl’s immaculate mother and her admonishment to keep clean was too unsettling. Taking a deep breath, Lucy crossed to where the girl was standing and squatted down in front of her.

“I’m sorry, Kate,” she said, watching the small, unhappy face in concern. “I didn’t mean to scare you or to hurt. I just saw where you’d gotten some paint on the back of your arm and was trying to wash it off.” She paused, wanting to communicate the urgency she felt without frightening the girl further. “Don’t you think we’d better try to get it clean before you go home?”

Kate hesitated, then nodded, and followed her back to the sink. Once more, gently, Lucy scrubbed at the purplish smear. This time Kate bore it soundlessly, head down. After some effort Lucy realized the adjacent skin on the girl’s arm was beginning to turn pink from the abrasion, though the paint wasn’t coming off. She checked the towel — a hole was wearing through the damp brown paper, but there was no paint on it at all. She glanced again at the purplish splotch on Kate’s arm, parallel stripes like fingers. There was a roaring in her ears —

The pressure didn’t advance in a wave this time, but came into existence suddenly and relentlessly all around her, as though the very air had turned to water and was drowning her in silvery darkness. Desperately Lucy tried to push it away, with no more effect than if she had been pushing water. There were voices in her head, voices she didn’t want to hear. She tried to shut them out, but they were all around and through her, pleading, no no please don’t please no … and there was pain oh god the pain …

When she came back to herself, she was huddled on the floor, kneeling doubled over with her elbows tucked into her stomach and her hands clutching either side of her head. She had no memory of assuming that position, no idea even how long she’d been like that. Her face was wet, and as she became aware of the silence around her, she realized she didn’t know if she had been sobbing aloud, or speaking, or had made any sound at all. And that realization, that total loss of continuity, was more coldly terrifying than the pressure itself.

She looked up. All the kids were staring at her with varying expressions of shock and concern and dismay. Lisa looked like she was about to cry. Kate was standing several feet away, hugging her arms tightly to herself, eyes wide. The silence was total, and it held her frozen for a long moment, knowing that every second would frighten them more but still unable to speak.

Then she took a small breath, and a bigger one, and found her voice again. “It’s okay,” she told them, trying to sound gentle and firm. “I just had a very bad headache all of a sudden, but I’m okay now.” It occurred to Lucy that at least she must not have screamed, or else Margaret would have come in to see what was wrong. The thought brought more panic than relief.

Andy slid out of his seat and crossed the room, knelt down next to her and began patting her back. Lucy smiled self-consciously at him, touched and embarrassed both. “Thank you, Andy.” She took a deep breath and stood up. The room dipped and she blinked against the dizziness.

Looking at the wall clock, Lucy made the decision to go ahead with lunch. It was a little early yet, but she honestly didn’t think she could direct any sort of activity at this point. The kids pulled out their lunchboxes and ate, speaking in subdued whispers.

After lunch was naptime, and Lucy had an hour in which to pull herself together. She couldn’t calm down, though; thoughts chased each other in her head, snapping with their sharp teeth.

What if she were crazy? She’d lose her job for sure. Lucy had been glad to get this job, even though it didn’t pay much, because she liked working with kids. The kids liked her, too — it was, finally, something she was good at. Maybe the only thing she was good at. She’d been fired from two waitress jobs already; she couldn’t seem to keep all the dozens of things straight in her head, and all the yelling and crashing of dishes in the kitchens panicked and paralyzed her.

She’d thought this job would be different. Oh, the kids could be loud, but their high voices never alarmed her in the same way. She sometimes didn’t deal so capably with their parents, but Margaret took care of that side of things. Everything had been going well. For the first time in her life she’d maybe started to feel proud of herself — and now she was messing it up again, the way she always did. Lucy held back a sob of frustration, not wanting to disturb the kids on their floor mats, but the tears ran down her face unhindered.

Tentatively, she circled back again and again to that time she couldn’t remember, but it remained a dark hole in her mind, a bottomless chasm with no bridge across it. It terrified her. She could remember forwards through the fingerpainting, washing the kids up and Kate last — and then her mind sheered away from itself, from the edge of that dark fissure.

The pressure hovered, silvery-gray, at the edges of her mind. She’d felt it occasionally for about a month now, but she could no longer deny that it was getting both worse and more frequent. Now she was even hearing voices. People who heard voices were crazy.

She’d have to quit, she realized. She was responsible for the safety of ten kids. if she lost control like that again — anything could happen while she was blacked out. They could get hurt. She might even accidentally — Lucy veered away from that thought before she’d even finished it. It led to places she didn’t want to go.

So she’d have to start looking for another job. The thought of waitressing again made her stomach knot up. But she couldn’t afford the sort of clothes she’d need to work in an office, and she doubted anyone would hire her without experience or a college degree, anyway.

Suddenly thinking about it further was just too painful. Lucy picked up her novel and tried to lose herself in it until it was time for the kids to get up.

The rest of the afternoon went smoothly, as though nothing had changed. At storytime, Lucy read aloud from “The Patchwork Girl of Oz.” The kids were entranced by the tough, wisely nonsensical Scraps, and the Glass Cat’s single-minded obsession with her own pink brains (“You can see ’em work”) brought gales of giggles with every repetition. Lucy finished the customary two chapters, and when the kids begged her to keep going she continued with a third. After that, she turned them all loose to play with blocks and dolls and crayons and puzzles.

Five-thirty came quickly, and for several minutes the tin bell on the front door jangled almost nonstop as parents came in to collect their kids and left again. Lucy had her hands full matching up fingerpaintings and lunchboxes with their owners. What a mess it will be, she thought, when the weather turns cold and we have jackets and gloves to deal with as well. Then she remembered, like a punch in the stomach, that she wouldn’t be here that long.

Lucy waved goodbye to Amy’s dad, then glanced around the room. Only Kate was left. The girl was kneeling down in a little hump, her arms hugged around herself and her head on the floor turned sideways, staring.

Lucy swallowed hard, her heart thumping in recognition. She sat down crosslegged on the floor nearby. “Kate?” She hesitated. “Are you — do you see the colors?”

Kate didn’t answer, didn’t move her head at all or even blink. She just stared out across the carpet, unfocused. Lucy began to be concerned. She considered touching the girl to rouse her, but held back at the thought that Kate might react by flinching away or even screaming.

Very slowly, Lucy began to mirror Kate’s posture. She rose up, unfolding her legs and tucking them beneath her, then began to bend forward over her knees. A lock of hair fell down across her mouth, and Lucy pulled it back behind her neck without taking her eyes from Kate’s face. She lowered her head until her cheek rested flat on the rough carpet, and her eyes were opposite Kate’s brown ones. The colors were there, all around her, rose and saffron and turquoise. Falling into them was temptingly easy, but she resisted, concentrating instead on Kate’s eyes. They were like polished amber, deep warm brown with gold glimmers and rays around the center, framed by long feathery eyelashes. And Lucy saw them swim back into focus, pull away from whatever far country they travelled, until they gazed into her own eyes, and blinked.

“Hi,” Lucy said, very softly, and smiled.

To her shock and joy, Kate smiled back. It was a tremulous thing at first, a quiver of the lips on one side only, but it made Lucy so relieved and happy that she broke out in a full grin. And in a moment Kate was smiling too, so broadly that her eyes crinkled up and nearly disappeared. She let out a high, tiny giggle, and in a moment they were both lying on the floor laughing out loud over nothing at all.

Finally it died away, and they sat up together and caught their breath. Lucy ran a hand lightly over the top of the carpet. “The colors are pretty, aren’t they?”

Kate nodded. “Sometimes at home I have to stay in the corner for a long long time, and I watch the colors in the floor. Or I make up colors in my head if it’s dark like in the closet.” Her voice was quiet and matter-of-fact. “But these are better.” She put a hand down and rubbed the nubby pile back and forth with her small fingers.

Once again, the pressure engulfed her. Lucy had almost expected it this time; she gripped her knees until her fingertips turned white and fought to push it back, to retain control. A vision blossomed in her brain, a thin yellow crack of light leaking under a closed door, and darkness all around. Tears welled up in her eyes and she turned away, both to hide them and to escape from the picture in her mind.

Only a minute later, it struck her how this gesture musthave seemed like a rejection to Kate, and so she turned back. But the girl had pulled one of the picture books from the shelf and was absorbed in it. Lucy’s heart sank to see the expression on her face — as closed in on itself as fingers, or a flower at dusk.

Lucy wiped her cheeks dry with both hands and searched for some way to recover the connection. “Do you want me to read that to you?” she offered.

“No, thank you,” said Kate with careful politeness. “I can read it myself.”

Lucy was startled and a little skeptical. She was pretty sure Margaret had told her earlier that Kate was only four, and though the book had lots of intricate, eloquent pictures, she thought much of the text would have baffled a bright second-grader. “Well, would you read it to me, then?”

Kate nodded, turned back to the first page and began reading in her quiet voice, only stumbling a little over some of the stranger proper names. Lucy had to make a special effort to keep her jaw from dropping.

They were almost halfway through the book when Margaret entered the room. Kate fell immediately silent, and Lucy whispered, “I’ll be right back.” She stood up and crossed to the door where Margaret waited.

“I just got a phone call from Ellen Bartholomew,” Margaret said, low enough that Kate couldn’t hear. “Or, rather, Ellen Bartholomew’s secretary, who said that Ellen was tied up in a meeting and would be late to pick up Katie. As if that weren’t already obvious,” she added, rolling her eyes toward where Kate sat, still turning pages.

Margaret paused and stared at Lucy more closely. A frown puckered between her thin eyebrows. “You look exhausted. Listen, why don’t you go on home. I’ll stay with Katie until her mother comes.”

Lucy hesitated. She wanted to stay with Kate, but the thought of dealing with Kate’s mother again, without Margaret, twisted her stomach. “Okay. Be sure and tell her mother — tell her Kate was very well-behaved. There were no problems at all.”

Margaret nodded. “All right. Try to get a good night’s sleep, okay?”

“Yeah.” Lucy grabbed her novel from the desk and glanced around the room, stooping to pick up a stray crayon.

Margaret held out her hand. “Here. I’ll take care of cleaning up. Really. Just go home.”

Lucy handed over the crayon and returned to the bookshelves. “I have to go home now, Kate,” she said, and did not add, as she would have with another child, that her mother would be there soon. Kate shot her an anxious look that made her heart turn over.

“I’ll be back tomorrow,” Lucy offered. “I’ll see you in the morning, first thing, okay? You can finish reading me the book.” She felt instinctively that this was the right thing to say, that it was what Kate needed to hear, yet she felt a chill as she heard the words come out of her mouth, thinking of her earlier decision to quit. Surely it was cruel to befriend the child when she knew she would soon have to abandon her? But Kate seemed to need a friend so badly, and how could she ignore that? Lucy didn’t know how to reconcile the paradox of responsibilities.

Kate looked unhappy, but nodded. On impulse, Lucy risked patting the girl’s shoulder, and was encouraged when Kate allowed it without pulling away.

The tin bell on the outer door clattered as it shut behind her. Lucy crossed her arms over her stomach, feeling a wrench, as though she’d left part of herself curled up on the carpet in the quiet classroom.

Instead of going directly home, Lucy turned and walked in the opposite direction, toward the little urban park where she’d taken the kids a couple of times on sunny afternoons. Today had been overcast, but the clouds had marched on and now hung in a line to the east. In the west the sun shone brightly in a pale sky, obscured only by the occasional tree.

The park was almost empty. At the far end, a man tossed a ball for a spotted dog and talked to a punk teenage girl in a black leather jacket. Three kids, two grade-school boys and a smaller girl, played around the sand pit and the jungle gym, and two women sat chatting on a bench nearby. Lucy walked on past the playground until the kids’ yells were faint enough she could block them out. Then she stuck her hands in the pockets of her jeans and leaned up against a tree trunk, closing her eyes. The sun was warm on her face, tinting the insides of her eyelids red-orange. Lucy took a deep breath, smelling the green smell of grass and trees and trying to shut out the sharp stink of car exhaust and new asphalt.

“Hey, have you seen my doggie?”

Startled, Lucy opened her eyes, blinking against the sun. The punk teenager, a girl of maybe fifteen or sixteen, was standing off to one side, arms straight and hands clasped behind her back. She was wearing ripped fishnet tights, some sort of low-cut red shirt just visible under the leather jacket, and a flouncy, apple-green miniskirt. Her hair was pale blond and shaved very close to her skull except for a hot pink forelock that fell curling over one eye. “Hi,” she said solemnly, staring until Lucy broke out in goosebumps and shivered. Yet she couldn’t look away.

“Hi,” she said back.

Suddenly the girl grinned. “Wow, your head is all full of pretty colors.” Lucy decided she looked younger than she’d first thought, maybe twelve or thirteen. “Like a kaleidoscope,” the girl continued, “all jumbled and swirly. Or an imbroglio.” She pulled a long strand of blond hair out over her ear and began twisting it around her finger. “My sister gave me a kaleidoscope once. I forgot where I put it though. He’s kind of black and brownish, with pointy ears. The kind that stick up.” She held her hands cupped on top of her head to demonstrate.

Lucy blinked, trying to catch up. “Your dog?”

“Well, he’s not my doggie really, I mean my brother sort of gave him to me, or at least told us we were s’posed to stay together. Um.” Her forehead wrinkled and she looked uncomfortable. Up the street a car horn blared.

Lucy shook her head. “I haven’t seen him. I’m sorry.”

The girl smiled again. “That’s okay. Destiny said I’d find him, and he knows everything. Except for a couple of things that I know that he doesn’t. Don’t you think it’s a pretty word?”

“— What?”

“Imbroglio. That’s what the doggie said my realm was. He’s very clever.”

“I like ‘marmalade,'” Lucy offered. “And ‘wobble.'”

“Wobble’s nice.” She grinned. “I think you’re nice.” The girl cocked her head like a puppy. “What’s your name?”

“Lucy.”

“My name’s Del. Except that’s not really my whole name, but I don’t like to say my whole name out loud and anyway it changes. Is Lucy your whole name or just a part?”

Lucy considered. “Well, just a part, I guess. But I don’t like to say my whole name either,” she added hastily, to stop the girl from asking.

“I like Del ’cause that’s what my brother always called me. I looked for him too, and I found him, only then he went away again. But first he gave me coffee. It was icky.” She scrunched her face up.

Lucy laughed. Weird, she thought, definitely weird, but endearing.

“Look.” Del bent over abruptly, like an out-of-control marionette. One hand swooped down and plucked a stalk of dandelion fluff out of the grass. She straightened up and held it out to Lucy. “Here.”

Lucy took hold of the stem. The other girl’s hands were small, the fingernails bitten short and ragged like her own. Del picked a second stalk and tickled the end of her nose with the fuzzy tip. Then she glanced over at Lucy. “Well, you have to blow on it, silly! Blow as hard as you can.”

Obediently, Lucy took a deep breath and blew on the dandelion head. Tiny feathery parachutes scattered and spun out in an expanding cloud. Lucy watched them all, her eyes flicking from one seed to the next as they dipped and drifted in the wind.

Beside her, Del blew out so sharply it was almost a whistle. Lucy glanced over, a little startled to see her fluff behaving differently. It fluttered and sparkled like glitter, and it fell up. Del, frowning at the naked head of her own stem, appeared not to notice this.

“What’s the word for when you used to love somebody and now you don’t anymore but every time you look at them you remember sort of that you used to love them?”

Lucy shook her head, smiling bemusedly. “I don’t know.”

Del dropped her stem, walked over and peered at the stalk Lucy still held. Lucy looked down. One thin brown seed with its white shock of hair still stuck to the top.

“Hey, you get a wish!” Del pirouetted once, her red-orange hair fanning out around her head. Sunlight glinted off the zippers on her jacket, sharply white. “Neato! Whatcha gonna wish for?”

A wish? Lucy’s mind went blank. What did she have to wish for? “A blue pumpkin,” she said. “And a glass cat with pink brains.” She smiled wryly at her own whimsy.

“Oooh!” The girl’s eyes widened. “That’s good!” Lucy suddenly noticed that Del’s eyes were different colors. Her right eye, the one that the thin variegated braid kept falling over, was as apple-green as her skirt. But her left eye was pale blue and shimmery. Staring into it, Lucy was reminded of something, though exactly what kept slipping out of her grasp.

“I counted all my feathers once,” Del said. “I had six hundred and twenty-two.”

The memory clicked into place. “Sequins,” Lucy blurted.

“Really? How many?”

Lucy gave a small shrug, still dazed. “I don’t know. Hundreds. Or maybe thousands. On this pale blue dress my mother had when I was little. She called me into her room, and she was wearing this dress, and she …” Abruptly her head filled up with the pressure again and she swayed and sat down hard on the ground. It receded quickly this time, but it left Lucy so weary and frustrated that she began to sob anyway, her shoulders shaking.

Del squatted down next to her, hugging her arms around her ankles. Both bony knees poked through gashes in her fishnet tights. She smelled strange, though not unpleasant, like sour sweat and roses. “You’re having a really bad day, aren’t you?”

Lucy took a deep shuddering breath and nodded, swallowing past the lump in her throat. “Everything keeps pressing in on me.”

“I have days like that all the time. I kept going all butterflies, before. And fishies. I couldn’t help it.” She sat down and put her elbows on the ground and her chin in her hands where she could look up at Lucy. “Sometimes it’s too hard to hold everything together. I think it used to be easier but I’m not sure. Maybe you could be fishies for a while instead.”

Lucy shook her head, wiping roughly at her cheeks. “I can’t, though. They … there’s this little girl. Her name’s Kate. And I think … I think she needs me. I’ve got to pull myself together, or —” Her eyes filled with tears again.

Del nodded gravely. “My brother Dream went all splooey once.” She wiggled her fingers. “And I had to. Um.” Her chin quivered. “It hurt a lot. But I had to help him. He was my friend.”

“Yeah,” Lucy said, thoughtfully. “Sometimes you can do stuff to help someone else that you would never do for yourself.”

Del’s brow furrowed, then cleared. “I know!” she said, sitting upright. “I could give you a song. I did that once before. I saw this man with the very saddest face, and it made me sad too, so I gave him a happy song to cheer him up. One of the ones where the end is the same as the beginning so it goes around and around and around like a — whatchacallit. With the horsies.”

“A carousel?”

“Yeah!” She grinned happily. “Like a carousel. I put it in his head so he would remember it for ever and ever. You want me to put a song in your head? I’d pick a really pretty one.”

Lucy blinked. “No, I don’t think so, thank you,” she said carefully.

“Okay.” Del pulled a lock of lime green hair forward from the nape of her neck and put the ends of it in her mouth.

Lucy let her breath out slowly. “The problem is, I keep getting this — this pressure in my head. It’s like everything goes all silvery and I lose track of where I am or what’s happening. And the worst part is, I don’t know why it happens, so I can’t control it, or even prepare for it. And now it’s getting worse,” she finished miserably.

“But you do know why.” Del blinked at her solemnly. “You just forgot that you knew. Only now you’re starting to remember that you forgot.” She plucked a blade of grass and held it up so that she was looking at it nearly cross-eyed. “If I were going to make coffee, I’d make it taste good. Like pumpkin pie.”

Lucy pulled back and stared at the girl. “What do you mean?” Her voice skirled upwards in panic. “I don’t know why this keeps happening to me. I don’t know what’s wrong!”

“It’s okay,” Del said. “You needed to have it that way. Sometimes you gotta pretend not to know stuff just to keep going.” She opened her fingers and a green dragonfly flew off, dipping drunkenly. “Only, you can’t pretend forever and ever. It’s too hard.”

“But why is it happening now?” Lucy wailed. “Everything was fine before!”

Del tilted her head, biting at a fingernail. “You know what the word is for things not being the same always? I do. It’s ‘change.’ I asked Dream that and he told me and I remembered.”

Lucy opened her mouth to protest, then stopped and thought about that. She’d been feeling the pressure for about a month — what had changed a month ago?

And then she knew. “Del?” she said, her heart pounding.

Now dragonflies were crawling out from under the lapels of Del’s jacket, narrow blood-red bodies and ocean-blue, and papery-thin wings that blurred into nothing as they swooped off. “Uh-huh?”

“My whole name.” She forced the words out. “My whole name is Lucianna Eileen Turnbridge.” The silver pressure was so tight and near she could see it from the corners of her eyes, rippling like sunlight on water. “Eileen … is my mother’s name. Was her name. She died last month.”

Del shed a few more dragonflies and didn’t say anything.

“I didn’t even cry. I must be really awful, I mean, I cry at the drop of a hat, but not when I found out my mother died. I wasn’t even truly sad. Just … relieved. That she wouldn’t be around to hurt me any more.” Lucy burst into tears. She hadn’t planned to say that out loud at all, hadn’t even let herself think it until now. She sat and hugged her arms around herself and rocked, sobbing and sobbing for all the old hurts and the relief from fear.

“Hey, are you okay?” Del said diffidently, after a little while. “I’m sorry. I’d touch you, but …” Her lip quivered, and the mismatched eyes filled with tears. “But I don’t think you’d like it. I don’t want to hurt you.”

Lucy suddenly realized she was bawling in front of a total stranger, a kid no less, and the embarrassment helped her regain control. “It’s okay. I’ll be okay.” She tried to take a deep breath and coughed instead. “I’m sorry. I don’t know why I gabbled on like that. You don’t even know me. I’m sorry. I guess I just needed to talk to somebody.”

“I talk to lots of people. Lots and lots. Most of them don’t understand me though. My brother came to see me once when I was mad.”

Lucy shrugged. “I never had any family, except my mother.”

“That’s sad. I’d be really sad if I lost my whole family. Desire’s kinda mean sometimes and Despair and Dream can be pretty scary, and I don’t see my other sister much ’cause she’s so busy and Destiny’s kinda, I dunno. Distant. But at least they’re there so I don’t get so lonely.” She hugged her arms to herself, suddenly frail. Lucy was reminded of Kate. “Except I get lonely anyway,” Del continued in a small voice, looking down.

A wave of tenderness and pity washed over Lucy. The girl was so confused and forlorn. “I’ll be your friend,” she said softly.

Del looked up, hope lighting her face. “You will? Really?”

Lucy nodded.

“Oh, goody!” She clapped her hands in delight. “Then you can come live with me in my realm and we can make stuff up and sing songs and we’ll find my doggie and the three of us will be happy forever and ever and I’ll never be lonesome again.”

Oh dear, thought Lucy in alarm. She shook her head. “I can’t,” she said gently. “You know I can’t.”

Del frowned anxiously. “But. You said you’d be my friend,” she pleaded.

“I will. But I can’t go away with you. I have to stay here so I can be Kate’s friend too.” Well, Lucy thought, I guess I’m not quitting my job. Something eased in her chest at the decision.

Del sighed unhappily and looked away. “You were wrong. You know. About what you said before.” Her tone was hurt.

Lucy frowned. “What?”

“You said I didn’t even know you. But I do.” Del tilted her head back and began blowing spit bubbles. Lucy watched her lips, fascinated, as the bubbles changed colors. Green blue indigo purple. Pop. “You’ve always belonged to me.” Purple magenta red. Pop. “Where did you think all the colors came from?”

A drop of spit trickled red from the corner of Del’s mouth. Lucy looked away, uneasy. The sun was low between the buildings and tinged with orange. A gust of cool wind lifted the hair on Lucy’s arms, and she shivered. “I should go home,” she said.

“Okay,” Del said, still hurt. She blew an orange bubble.

Lucy got to her feet, brushing bits of grass from her jeans, and then just stood there for an awkward moment while she searched for a way to say goodbye. “Good luck finding your dog.”

Yellow green pop. Del lifted her head. Her shaggy hair fell around her face, cherry-red. “Lucy.” The mismatched eyes looked into hers, serious and wise in a way that made Lucy wonder how old Del really was, after all. “It never stops hurting. But we can see things nobody else lets themselves see.” Then she grinned, looking like a child again. “I’m glad you’re my friend anyway. Maybe after I find my doggie maybe I’ll bring him here to meet you.”

“I’d like that,” said Lucy, smiling. She waved goodbye and started walking back toward the playground and home.

As she passed the block where the daycare was, she turned on impulse and walked down it. The t-shirts that Matthew and Kate had worn to fingerpaint in would have to be washed, and Lucy was pretty sure she was going to have to do laundry tonight anyway. She thought she was out of underwear.

She dug the keys out of her jeans pocket and unlocked the door. There was just enough reddish light from the sunset for her to navigate the hallway, but the classroom with its east-facing windows was night-dark. Lucy flipped on the lightswitch. It occurred to her then that she had never seen the room except in daylight. It seemed strange, and too quiet.

She pulled the two t-shirts from the box of clothes, and grabbed a couple more that looked dirty enough they must have been overlooked the last time. On her way out, she noticed a large piece of paper lying on one of the round tables. Curious, she veered toward it and saw that it was Kate’s fingerpainting. “Oh, damn,” she said aloud. Of course Margaret didn’t think to make sure Kate took it with her.

Well, it wasn’t the end of the world. She’d just send it home with Kate tomorrow. It was really very ugly, she thought ruefully, stepping closer to look again at the huge muddy swirl the color of a — it looked like a —

Her mind stopped. Suddenly Lucy was irritated and impatient. Say it, she told herself firmly.

“Like a bruise,” she whispered into the empty room. Like the marks on Kate’s arm, which hadn’t been paint at all. Lucy felt dizzy and sat down on one of the small plastic chairs without really noticing, without looking away from the paper.

We can see things nobody else lets themselves see, she thought. Like colors in the carpet. Like the intention of cats and pumpkins behind a child’s smeary painting. Like a bruise on a child’s arm, or misery and horror in her eyes.

Lucy took a deep breath, bracing herself, and focused on Kate’s picture in that particular way, the way that revealed all the different colors in the carpet. Immediately she was drowning again in silvery darkness. A slap stung her cheek, and a woman’s voice yelled at her, furious and incomprehensible. She crouched in a small dark place, huddled in upon herself against the pain confusion fear chaos hurt terror pain …

Lucy came back to herself staring at a whorl of yellow green turquoise orange blue purple red. She blinked, and they swirled together into the muddy bruised color once more.

“Oh god,” she whispered. “Oh, my god. I’ll get you out, Kate, I swear it.” And she buried her face in her hands, and cried.

Arriving home a little while later, Lucy unlocked the door to her apartment, flipped on the light switch and then stopped short. A fat blue pumpkin squatted on the low coffee table in front of the couch. Sitting next to it was a delicate glass cat, one paw raised as though she had been frozen in the act of washing her face. She had emerald green eyes, a ruby red heart, and pink jewel brains. You can see ’em work, Lucy thought, and chuckled in delight.

The tip of the cat’s spun-glass tail twitched once, irritably, and then was still.

Karawynn Long’s notes:

The story behind the story …

Some time in the summer of 1994 Neil Gaiman sent me an email inviting me to write a story for the Sandman anthology he was co-editing. Or, more precisely, he sent me an email wondering why he hadn’t already received a story from me.

Well, because you never asked me to write one, I replied, somewhat bemused.

I didn’t? he said. Damn. Bugger. Would you like to write a story for the Sandman anthology?

I’d be delighted, I said.

Of course it wasn’t nearly that simple. I had to get one of the other editors to mail me the guidelines, and it took him two months to do so, compounded by the fact that I’d moved in the interim and was having my mail forwarded. And then I had to actually come up with a story. “Do me something cool and special and something only you can do and make it a cool and wonderful story,” Neil said.

Right. No pressure there.

For some reason, my brain kept trying to incorporate neurological disorders into the story. I thought about writing something around Dream and narcolepsy, or Shivering Jemmy and autism. I had all the Sandman collections that had been published in paperback; I reread them all and then borrowed the Brief Lives issues from a sweetheart.

It didn’t take long then for Delirium to become my favorite of Neil’s characters. I was enchanted by her silliness, moved by her sadness, and disturbed by her unexplained past. What terrible thing could have caused the incarnation of Delight to become the personification of Delirium?

Some of the things she said made me shiver with recognition. I had an idea.

Life got a little crazy. I had to move out of my new apartment on short notice, under threats of physical violence from my roommate. And right on the heels of this I discovered that the sweetheart I so adored had lied horribly to me and others, and our relationship went up in a mushroom cloud.

When I began, ever so slightly, to pull myself together again, the first thing I began to do was write the Sandman story. I finished it and turned it in to Neil; he asked for revisions; I rewrote it and gave it back. This time Neil accepted it for the book.

Of course, it wasn’t nearly that simple. In the interim, some of the other authors had begun to receive contracts from DC Comics, and were very disturbed. The terms under which we’d been asked to write the stories bore no resemblance to the terms in the contracts that were actually sent. Neil tried to negotiate DC back to where they were supposed to be. The authors waited.

Almost a full year later he gave up, having made very little headway. There had been some talk of moving the anthology to another publisher, removing all the DC-copyrighted names, and selling it as “Neil Gaiman’s Dream World” or somesuch. But too many authors had already signed the nasty DC contracts to make this feasible. Several of the remaining authors withdrew their stories from the book (and later rewrote the Sandman characters out of them, and sold them to other markets). I was despondent, however, because I felt in my story the Delirium character was too integral to cut. I waited to withdraw the story until I’d read the contract for myself, though. (Michael Berry is another author in a similar boat. You can read his Merv Pumpkinhead story on his web page. Somewhere in Lucien’s Library there is a very different Sandman anthology than the one which eventually saw print.)

I moved across the country and for a while was distracted with the logistics of that. Eventually it dawned on me that even so, I should have gotten the contracts long since. I inquired of Neil, and of the other editor, and discovered that despite Neil’s acceptance, my story had never actually been forwarded to DC, and so was not currently included in the anthology.

Which is probably for the best, as it removed all temptation for me to sell out. Under the circumstances, though, my story is not likely to ever be professionally published. So there is no reason for me not to print it here. Well, I suppose there is the small possibility of a lawsuit from DC, but I won’t tell them if you won’t. It will make me feel better, less as though all my effort were wasted, if I know some people will have the opportunity to read it.

Despite the crazy heartbreak I was in at the time (or maybe a little because of it) I enjoyed writing Delirium. I hope you enjoy reading her. People familiar with Sandman and particularly with the Brief Lives arc will recognize many of the things that Delirium says, but non-Sandman readers have generally had no trouble following the story. Readers of L. Frank Baum and e.e. cummings will recognize bits as well. There’s even an obscure Tori Amos reference that I don’t expect anyone but me will ever notice. (If you think you know what it is, send me email and I’ll tell you if you’re right. There are several references to Tori song lyrics, but this is more obscure than that.)

One other tidbit: The original title for this story was “The Color of Her Countries” — a phrase taken from an e.e. cummings poem. The consensus of my writer’s workshop, though, was that the phrase had been forever ruined by association with the Piers Anthony novel The Color of Her Panties. So I reluctantly substituted another line from the same poem and it became “The Voice of Her Eyes.”

Naturally, the character of Delirium and the names of the other Endless (Destiny, Dream, Death, Destruction, Desire, and Despair) are all © DC Comics. The story itself and all other characters are © Karawynn Long (1994). Delirium illustration at top © Karawynn Long (1996).

If you’d like to put a link to this story on another web page, please link to this introduction (http://www.sff.net/people/karawynn/delirium.htp) rather than to the actual story document. If you wish to copy or display the illustration at the top of the page, send me email. And finally, if you like the story and would like to read other things I’ve written, you can visit my writing site.

“It was then that Delirium noticed that she had absentmindedly transformed herself into a hundred and eleven perfect, tiny, multicolored fish. Each fish sang a different song. And as she put herself back together again, unable for the moment to remember whether the silver flecks went in the blue eye or the green one, she decided that a dog would be a nice thing to have. And then it occurred to her that there had been a dog around at some point, hadn’t there? A nice doggie. And she went off to look for it, trailing occasional fish …”

— Neil Gaiman, The Kindly Ones